Thursday, July 7, 2022 03:00 AM

Source: Bloomberg, Coner Sen

Checking in on the health of the economy used to mean a quick glance at a handful of indicators: unemployment and inflation rates, a couple quarters of gross domestic product growth, housing market sales, maybe the recent performance of the stock market. That approach isn’t as useful here in the middle of 2022.

For reasons including the unwinding of pandemic behaviors, changes in monetary policy and the energy supply shock from Russia’s war on Ukraine, the data is a mess right now.

So it’s understandable that many Americans believe the US economy is already in recession. The tracking model from the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank projects that real GDP growth in the second quarter will be negative. If that’s right, following on a 1.6% decline in the first quarter, it would trigger the oft-repeated rule of thumb that calls a recession after two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth.

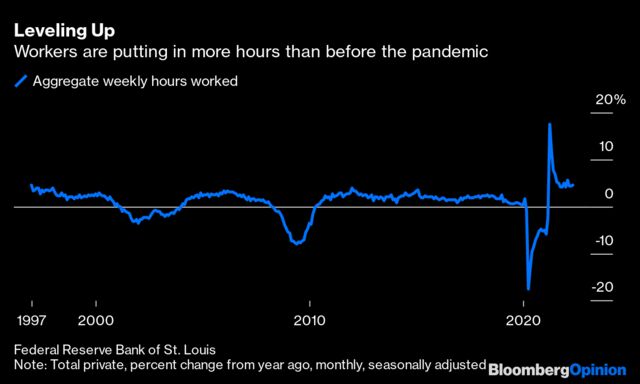

But not so fast. Ultimately, it’s up to the National Bureau of Economic Research to officially declare a recession. And until then, it’s the labor market that’s providing the most accurate picture of our economy’s health. For investors and business operators, the best metric to focus on is aggregate hours worked. In general, the more hours people are working, the higher their economic output, and for now, that metric is still pointing to robust growth rather than recession.

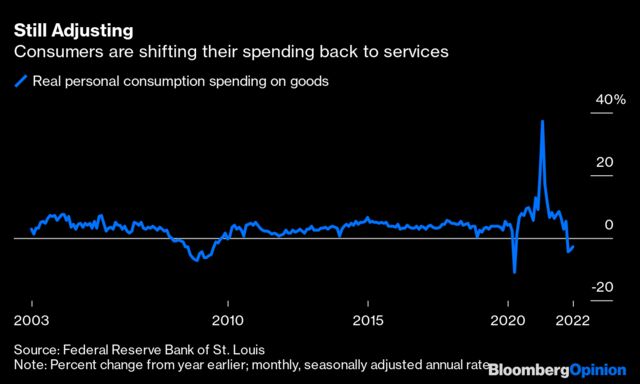

The main “hard data” indicator that’s consistent with recession is the growth in goods consumption, which, adjusted for inflation, is currently negative. It’s down 2.7% on a year-over-year basis, similar to what we saw in the summer of 2008 when the US economy was in recession. In an economy that’s 70% consumption, if Americans are buying less stuff than they were a year ago that’s a pretty good signal that the economy as a whole is struggling.

But the pandemic shifted the historic relationship between Americans’ consumption of goods and services, and it’s only begun shifting back since March or so. Goods consumption is down and spending on services is rising again. Retailers have a glut of inventory at the same time that airports and airlines are struggling under the weight of strong demand and staffing shortages, which have led to waves of flight cancellations and delays. Until we see some stability in the relationship between goods and services spending, it’s hard to rely on goods consumption as an economic signal as much as we would in normal times.

At a time when there are so many shocks rolling through the economy, the labor market is the best bellwether we’ve got to determine whether we’re in growth or contraction mode. But there have been pandemic and policy-related changes there, too, over the past year, so I would look at aggregate hours worked rather than measures of unemployment.

It feels like a long time ago, but it was just last May when the economy first began seeing staffing shortages as the Covid-19 vaccine rolled out and people began resuming more normal activities. There was a debate about whether stimulus benefits, including a boost to unemployment payouts, were keeping people from working. In May 2021, the annualized run rate of unemployment benefits was almost $500 billion compared with $19 billion in the recently released May 2022 report.

The labor market has come a long way over the past year. Aggregate hours worked, which includes both the number of workers and the length of the work week, is now up 4.6% year-over-year. People who were unemployed a year ago have gotten jobs. People who weren’t even in the labor force a year ago, perhaps because they feared Covid-19 or because of weak economic conditions, have re-entered the labor force and secured jobs. In May, total hours worked finally surpassed its pre-pandemic high, and it’s likely that we’ll see another new record in June.

Growth in hours worked signals that employers are still confident in future demand and workers have more income to help them cope with elevated inflation. In every recession going back 50 years we’ve seen hours worked shrink by at least 2%. We’re a long way from that at a time when Americans are still re-entering the labor force and employers continue to hire at a robust rate.

This can all change, of course, which is why it’s still important to track weekly data like the jobless claims report. But until this core labor market trend downshifts, any signs of economic weakness are probably due to pandemic-related rebalancing, one-off shocks, or simple noise in the data rather than a recession.