(Bloomberg Economics) —

At his press conference following the May FOMC meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell outlined the condition that would allow the committee to shift from 50-bps rate hikes to 25-bps: Inflation would have to come down on a sustained basis. One way that could happen is a large China demand shock that triggers sharp global financial tightening.

In 2015-’16, fears of a hard landing in China delayed the start and slowed the pace of Fed tightening. Could the same thing happen in 2022? Maybe, but things would still have to get a lot worse:

- The current situation in China is bleak. A lockdown in Shanghai, mass testing in Beijing, and fear of more problems to come have prompted a sharp downgrade in expectations. Bloomberg Economics’ China team has lowered its 2022 growth forecast to 3.6%, from 5.1%.

- For the U.S., what matters most is not how fast China grows but how financial markets react. In 2015-’16, China’s growth — at least based on the official data — was robust. It was the swing to global risk-off sentiment prompted by China hard-landing fears that caused the Fed to slow the pace of tightening, hiking only once — by 25 bps — in 2016, compared to expectations at the end of 2015 for 100 bps of tightening to come.

- According to the Fed’s SIGMA model, a 200-bps widening in BAA credit spreads could substitute for 75 bps of Fed tightening. From the trough in 2015 to the peak in 2016, the BAA spread widened about 100 bps. So far in 2022, it has moved up only 20 bps.

- That could change. More bad news on the scope and duration of China’s Covid lockdowns, or renewed fears about yuan weakness and capital outflows, could change market sentiment. For now, though, expectations of a sharp slowdown in Chinese growth have yet to translate into a major global risk-off moment.

- The China slump may also have a more direct impact on the U.S. inflation outlook. A 2% decline in the level of China’s GDP relative to baseline — close to our forecast downgrade — could send oil prices down 30%, according to Fed research. Right now, though, fears of a blow to Russian oil supply and a cut to Chinese demand appear to be offsetting, keeping oil prices around $100 a barrel.

- Using SHOK, Bloomberg Economics modeled a scenario where a sharp drop in Chinese growth takes 1% off global demand in 2Q 2022, knocks the price of oil down by $20/barrel, and leads to sharp dollar appreciation and widening of credit spreads. In that scenario, the model sees U.S. headline CPI falling 1.1 ppt compared to baseline and quarterly US GDP growth slowing to below 1% on an annualized basis in 3Q 2022.

- A China supply shock as lockdowns force factories and ports to operate at less than full capacity could add an additional inflationary impulse to goods prices. The supply shock is already evident in the Chinese data, but the timing and magnitude of the impact on U.S. prices is tough to gauge.

- Putting the pieces together, for now it would take a much larger widening in credit spreads, and downward moves in commodity prices as China demand slumps, to slow the pace of Fed tightening.

Fresh in the Memory — the 2015-’16 China Shock

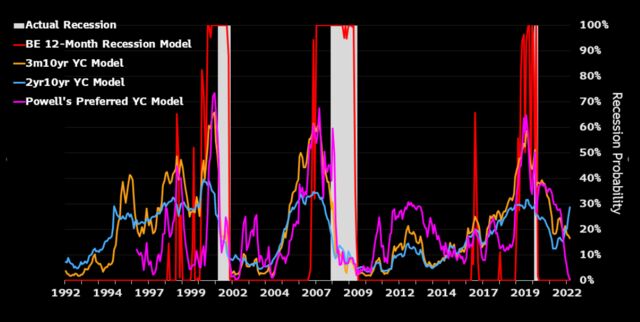

The experience of the 2015-’16 China shock will shape Powell’s and Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard’s thinking about the current situation.

- Back then, a swing to global risk-off sentiment triggered by China’s market slump, yuan drop, and capital outflows caused the Fed to slow its tightening. The FOMC hiked only once in 2016 — by 25 bps — compared to expectations at end-2015 for 100 bps of tightening.

- Brainard indicated financial tightening during that period substituted for 75 bps of rate hikes. The New York Fed’s DSGE model had a higher estimate, of about 100 basis points.

- Subsequent studies estimated that the delay in Fed rate hikes offset more than one percentage point of slowdown in U.S. GDP from the adverse global economic and financial developments induced by fears of a hard landing in China.

- Given that U.S. GDP growth slowed from 3.3% in the first quarter of 2015 to 0.5% by the end of the year, it’s likely that the Fed’s decision to slow its tightening was a critical factor in preventing recession. Powell could add 2016 to his roster of dates (1965, 1984 and 1994) when the Fed successfully engineering a soft landing.

Slower Fed Hikes Helped Achieve A Soft Landing in 2016

In 2022, China Lockdowns Yet to Spark Global Risk-Off Shock

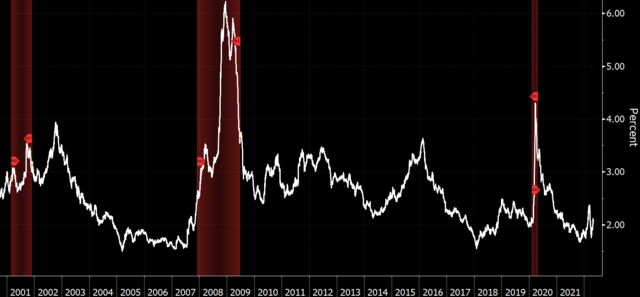

In contrast to 2015-’16, this year’s China slowdown hasn’t led to as sharp a deterioration in financial conditions. That means the Fed is less likely to see a need to slow its rate-hike pace.

- One of the most important components of financial conditions is the yield spread between BAA-rated corporate bonds and 10-year Treasurys, a variable that enters into both the Fed board model and New York Fed DSGE model. A widening spread means higher financing costs for firms, which can dampen activity quickly.

- In the 2015-’16 hard-landing episode, the spread widened by about 100 bps. In contrast — and somewhat surprisingly given the extreme situation in which China now finds itself — in 2022 the spread has widened by just 20 bps.

- Using a rough rule implied by the Fed’s SIGMA model, the widening in corporate spreads so far is not enough to substitute for even one 25-bps hike. Corporate spreads would need to widen by a further 200 bps to slow real GDP growth to below 1%, and potentially substitute for 75 bps of rate hikes.

Credit Spreads More Benign Than In 2015-’16

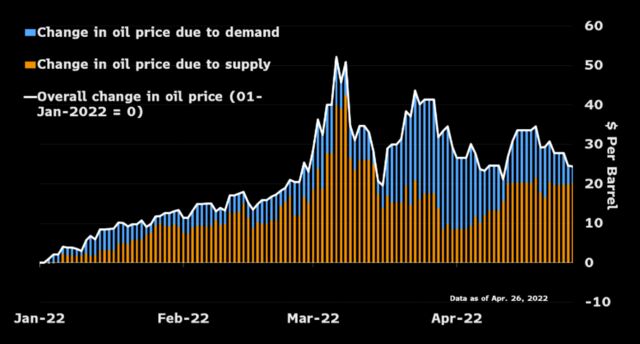

Adverse China Demand Shock Is Disinflationary

Fed research also has found China’s growth slowdowns to be disinflationary. A 2% decline in China’s GDP level relative to baseline could send prices of oil and metals 30% lower, and could shave about one percentage point from U.S. GDP growth in a year.

Right now, though, it appears fears of a negative shock to energy supply from Russia are roughly offsetting concerns about weak demand from China. That’s likely one reason why oil prices are lingering around $100 a barrel, defying predictions that the Ukraine war could push them close to $200 a barrel.

Lower Demand From China Keeping a Lid On Oil Prices

Offsetting Supply Shock From China

The net impact on U.S. inflation also depends on how much China’s lockdown disrupts production. The picture will be clearer in coming months. So far, latest PMI data suggest the contractions in China’s exports and domestic demand are a little more severe than the supply disruption. That suggests that even if lockdowns do snarl China’s supply chains, the net result of weaker demand and stalled supply could still be disinflationary.

Contraction More Severe in Demand Than Production in China PMI