(Bloomberg Economics) —

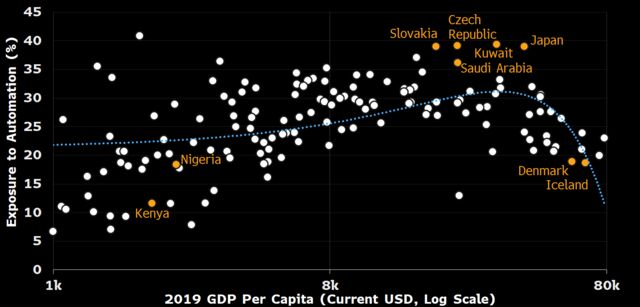

There’s a downside to automation. Worldwide, we estimate that 800 million people work in sectors where advances in technology place a significant share of jobs at risk. At a country level, the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Japan are most exposed to disruption from automation.

- Jobs that can be broken down into simple, routine tasks are easier to replace with machines than roles that require complex thinking, judgment or human interaction.

- This has been happening for decades, but the trend looks set to accelerate with advances in artificial intelligence, robotics and other technologies. We estimate that a quarter of jobs worldwide are in sectors with high exposure to being automated.

- Countries most exposed are the ones that have a large segment of their workforce in clerical support work (Japan), plant operations (the Czech Republic and Slovakia) or rely on cheap labor instead of machines to do routine tasks (the Gulf).

Who Is Most Exposed to Automation?

Source: Bloomberg Economics, International Labour Organization, World Bank

Automating Routines

Economists initially thought that machines tended to replace low-skilled jobs, but the thinking has evolved. Research by Maarten Goos, Alan Manning and Anna Salomons shows that automation tends to replace routine jobs — ones that can be broken down into simple, mechanical steps.

Occupations such as office clerks, machine operators and craft workers are more routine and prone to automation than livestock farmers, chief executives and (we’re hoping) economists.

Routine jobs are not related to the skill level. Instead, they tend to fall in the middle of the income distribution, as Goos, Manning and Salomons show. Automation can therefore create job polarization — the disappearance of the mid-earning roles — and higher income inequality.

How Many Jobs Are at Risk?

To estimate which countries are at risk from automation, we combine two elements:

- How routine each of the nine major ISCO employment categories are, using the work of Mitali Das and Benjamin Hilgenstock.

- The share of the workforce in every employment category using the International Labour Organization’s database for 176 countries.

For each country, we calculate the share of the workforce in the three most routine categories. A higher share means a higher exposure to automation. Our main results are:

- Nearly a quarter of the world’s jobs are in sectors with high exposure to replacement from automation. As a high-end estimate, this puts 800 million jobs at risk globally. Automation won’t annihilate these occupations completely but could threaten many of them.

- The Czech Republic, Slovakia and Japan are among high-income economies are most at risk — the share of routine jobs is almost 40% of the workforce. Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia also feature high up the list given their reliance on cheap foreign labor to do routine tasks.

- Luxembourg, Iceland and Denmark are among the least exposed — the share of routine jobs is less than a fifth of the workforce. Many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa also face low risk as the bulk of the workers are in elementary occupations that aren’t very prone to automation.

- For low-income countries, the fact that existing low-skill jobs are not exposed to automation could be cold comfort. With many factory jobs set to be automated, the path to move up the development ladder from agriculture to manufacturing may be blocked.

Our results have limits. For example, the degree of “routinization” varies within each employment category, as Das and Hilgenstock show. In Japan, for example, a high share of employment in clerical support may reflect a tendency of young workers to rotate through diverse roles within a given firm before becoming managers — and not all of those jobs are easy to automate.

But in the absence of a finer split of the distribution of employment in each country, our estimates serve as a useful proxy for exposure across countries.

Rage Against the Machine?

Some of the countries with the most to lose from routinization are among the most innovative. If the costs aren’t managed — with training and compensation for displaced workers — social stresses could slow the pace of technological change. For the economy, this poses risks similar to the backlash against globalization.

That said, a handful of countries with the highest exposure to routinization — Japan, the Czech Republic and Slovakia — also have rapidly aging populations. With the right policy mix, more robots could be exactly what’s needed to offset demographic headwinds.